Scrivener’s Dialogue Focus and Linguistic Focus tools let you view your work differently, and aid in revision and editing.

As your write in Scrivener, or when you get to the revision stage, you might want to focus on certain types of sentences and words to ensure that your writing sounds correct. When you write fiction, you especially want to pay attention to dialog; it should not only sound natural, but there should be a flow, a give and take among characters as they converse.

Scrivener’s Dialogue Focus tool gives you a close-up look at your dialog, so you can make sure it flows properly. And other Linguistic Focus tools, available in the Mac version of Scrivener, let you check how often you use different parts of speech: nouns, verbs, adverbs, etc.

In this article, I’ll show you how you can use these tools when writing and editing to make sure that your words sparkle.

Analyze your dialogue

Fiction is a combination of description and dialog. In some cases, there is more of the former – such as in the novels of Henry James – while fast-paced novels generally feature more dialogue. There’s a lot of latitude for the way descriptive texts are written, but dialog has to sound real, and it has to represent the give and take inherent in conversations, and not sound wooden and stilted. (Arguably, some of Henry James’s dialog sounds that way to us, more than 100 years after it was written.)

When people read a novel, they generally gloss over the dialog attribution (he said, she said), and just read the words in quotes. In sections where there is a lot of dialog, it is important that there be a natural flow in these conversations, whether they involve two people or more. It can be harder to ensure this with more than two people, and the dialogue attributions help identify the speakers, but nothing should break the rhythm of dialog sections in fiction.

Tip: a good book that will help you write better dialog is Robert McKee’s Dialogue.

Scrivener has a tool that lets you focus on your dialog. The Dialogue Focus tool dims all text that is not in quotes, so your dialogue stands out, but you can still see surrounding text in gray. This makes the dialogue jump off the page, so you can read it while easily ignoring descriptive text and dialog attributions, and check to see that it has the right rhythm.

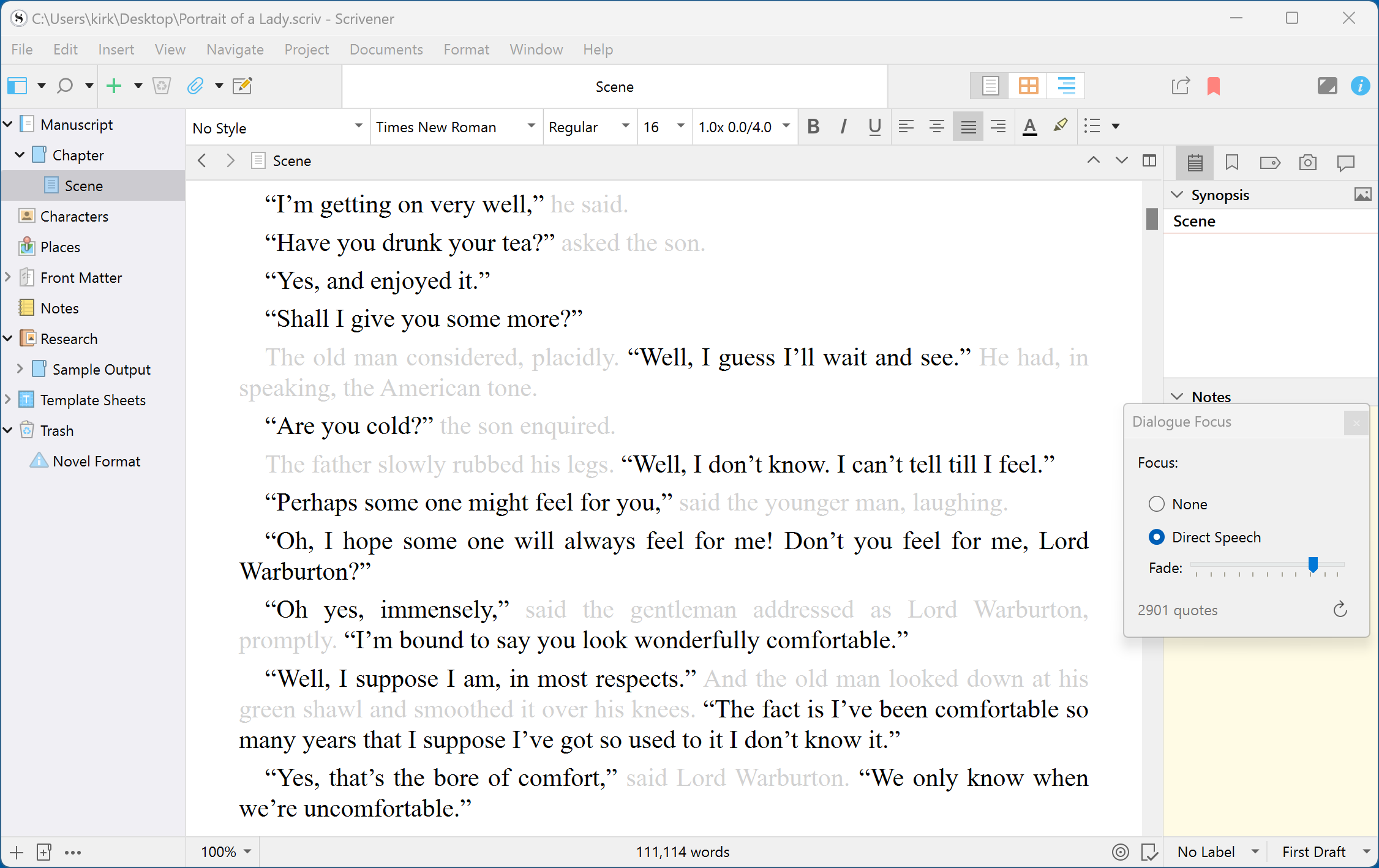

To use this, choose Edit > Writing Tools > Linguistic Focus (Mac) or Edit > Writing Tools > Dialogue Focus (Windows). Click Direct Speech, and Scrivener dims all the text that is not in quotes. Here is a section from Henry James’s A Portrait of a Lady:

You can adjust the dimming by dragging the Fade slider at the bottom of the small, floating window. If you click the circular arrow, this updates the display; do this if you’ve made edits to your dialog and want to see how it sounds.

You can read through your dialogue without being distracted by the rest of the text. Many writers like to do this out loud, to see how it sounds, and being able to skip the surrounding texts makes this easy.

To return to the normal view, click None, or close the small window.

Audit parts of speech

When editing, you may want to check how you use certain types of words. Scrivener’s word frequency statistics can show you how often you use specific words – see Use Scrivener’s Word Frequency Statistics to Refine Your Writing for more on using this tool – but this doesn’t tell you which types of words you use most often.

Checking how you use parts of speech can be important. Do you use a lot of nouns, not enough verbs, too many adjectives, or too many adverbs? Regarding the latter, it’s worth considering what Stephen King said in On Writing:

“I believe the road to hell is paved with adverbs, and I will shout it from the rooftops. To put it another way, they’re like dandelions. If you have one in your lawn, it looks pretty and unique. If you fail to root it out, however, you find five the next day… fifty the day after that… and then, my brothers and sisters, your lawn is totally, completely, and profligately covered with dandelions. By then you see them for the weeds they really are, but by then it’s—GASP!!—too late.”

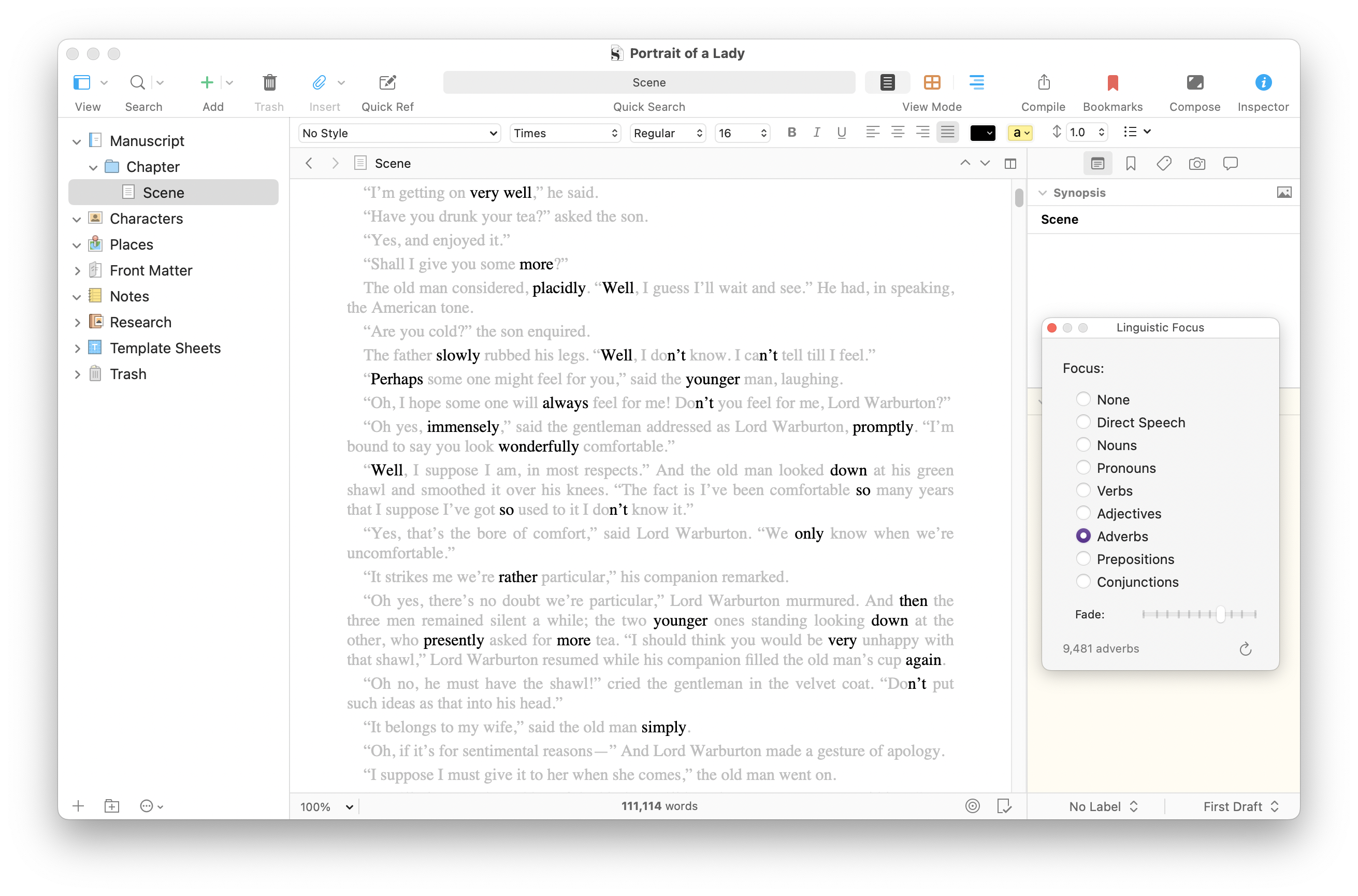

Adverbs are noticeable; often incredibly, terribly, eminently noticeable. Using Scrivener’s Linguistic Focus tool, on Mac (Edit > Writing Tools > Linguistic Focus) lets you see words of a specific type, with the remaining text dimmed, as with dialogue.

Looking at the same passage I used above to show dialogue, you can see that Mr. James did not feel the same way about adverbs as Mr. King.

Of course, not all of the highlighted words above are the type of adverbs that stand out. Words like well, more, so, and again are technically adverbs, but the kind that are like dandelions are the ones that end in -ly. Some are important, and you even see some in the dialogue above, such as immensely and wonderfully. These are words spoken by one of the characters. But the ones in dialog attributions – placidly, promptly, and simply – could, perhaps, be omitted.

As you can see above, you can also focus on nouns, pronouns, verbs, adjectives, prepositions, and conjunctions. If you look at your work with these various parts of speech selected, you may find that you overuse some of them, and this tool can help you scan your project, when editing, to remove those which are not needed.

As editing tools, both Dialogue Focus and Linguistic Focus allow you to view your work differently, zeroing in on elements that you may not be able to see as well in normal display. These tools help you ensure that you use the right words all throughout your work.

Kirk McElhearn is a writer, podcaster, and photographer. He is the author of Take Control of Scrivener, and host of the podcast Write Now with Scrivener.