It’s important to use the right words when writing, but sometimes it’s hard to find them.

Writing well is all about finding the right words. A simple, concise description is much more effective than one that drags on. Clear, authentic dialog is more realistic than long expositions. Sometimes, a single word, at the right place, can make all the difference between a middling story and a masterpiece.

Finding the right word isn’t always easy. Fortunately, we have some useful tools that can help us out.

The first draft

When writing the first draft of anything, it’s best to not worry too much about words. At this stage, you need to get your words on the page, and when you later edit your work, then you can find the right words. Stephen King has said that, when writing the first draft, “Any word you have to hunt for in a thesaurus is the wrong word.”

A good idea when you hit a speed bump in your draft, for words, descriptions, or dialogue that you can’t find quickly, is to use the journalistic convention of TK or TKTK, which means “to come.” it’s easy to spot this when editing, both visually and by searching in your document or project, and that’s when you pull out the dictionary or thesaurus to find the words that are just exactly right.

Dictionaries

I’m sure there are some writers who will say that they browsed dictionaries when they were young, but most of us hated dictionaries when we were in school. They were long, complicated to use, and often had tiny fonts. But the people who did browse dictionaries probably have impressive vocabularies, giving them a much more versatile toolbox when writing.

Dictionaries don’t help you find the right word, but they can confirm how words are used. If you’re not sure of the difference between insure and ensure, affect and effect, or stationary and stationery, the dictionary is your friend. Making the wrong choice among easily confused words isn’t a sin, but it does suggest that the writer isn’t paying attention.

These days, with auto-complete on our computers and other devices, it’s easy to make this sort of error, but when submitting an article or manuscript to an editor or agent, it’s best to have as few errors as possible. And when you self-publish, this is especially important, as you have no one to correct your writing. (Hint: pay an editor to go over your manuscript if you self-publish.)

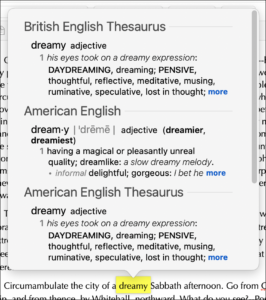

You can check the meaning of words directly from Scrivener. If you’re using Scrivener on the Mac, select a word, right-click, then choose Look Up (word). This opens a dictionary panel, which gives you access to a number of dictionaries and thesauri.

Scrivener for Windows has a similar feature, but since Windows doesn’t have a built-in dictionary, Scrivener uses an open-source dictionary. Select a word, right-click, then choose Dictionary to see the dictionary panel for the selected word.

You can, of course, use any online dictionary to check your words, if you have an internet connection, but don’t get distracted in your browser by shiny things.

Thesauri

In the 25 years that I’ve been working as a writer and translator, I’ve amassed a large collection of reference books. No book is more useful than a thesaurus. While I don’t often refer to one, there are times when I use a thesaurus to find precise words that aren’t on the tip of my tongue. While you can use online thesauri – or thesauruses if you prefer – I like having a book that I can browse, flitting from word to word. Here are my favorites.

- The Synonym Finder, by J. I. Rodale. First published in 1961, then updated in 1978, this book is a bit old, so it doesn’t contain contemporary terms related to technology. However, I’ve always found it to be the best, most efficient thesaurus for my writing. Words are listed in alphabetical order.

- Oxford American Writer’s Thesaurus, by Christine A. Linberg. An alphabetical thesaurus, this book also has “Choose the right word” sidebars, which explain the difference between similar words. This is useful for those who aren’t quite sure which synonym fits their context.

- Roget’s Thesaurus. Rather than a brand, this is a style of thesaurus, where words are grouped by concept, and you have to search the index to find which page to refer to. While this is a much slower tool, many writers prefer this approach. You’ll also find some Roget’s Thesaurus editions that are “in dictionary form,” which is a sort of hybrid.

- The Writer’s Digest Flip Dictionary, by Barbara Ann Kipfer. Both a thesaurus and a word list, this book contains synonyms for word combinations (such as sad, sad and discouraged, sad and mournful, sad and tearful), and word lists (such as names of oceans and seas, words for variants of the color red, and all those funny Greek-origin words for types of fear).

- The Thinker’s Thesaurus, by Peter E. Meltzer. This is not the type of thesaurus you want to use regularly, because it contains “sophisticated alternatives to common words.” However, if you have a character who speaks like a dictionary, this is where you find words like lentiginous, nocent, and subreption. It’s also good for crosswords.

Several of the above books are out of print, but easily available used from a variety of online sellers. I don’t recommend buying anything that is called a “student thesaurus” or a “collegiate thesaurus,” as these don’t have enough words for writers.

It’s a good idea to keep a thesaurus handy to spice up your writing. But it’s important to maintain balance; as Strunk and White said, you should write “using words and phrases that come readily at hand.” Over-reliance on a thesaurus risks making your writing sesquipedalian.

Kirk McElhearn is a writer, podcaster, and photographer. He is the author of Take Control of Scrivener, and host of the podcast Write Now with Scrivener.